The service station bathroom was dirty, it stank, and the walls were stained colors she didn’t want to think about, but it had running water and a soap dispenser, and that was all she needed. She soaped and scrubbed her hands for what seemed like an eternity, until her already-irritated skin was nearly bleeding, before finally rinsing with water hot enough that she winced in pain.

She stared at herself in the mirror while she dried her hands, the crack in the glass bifurcating her face into a strange, otherworldly visage she didn’t recognize. She shivered, and then immediately felt a pang of embarrassment. “Oh, get it together.”

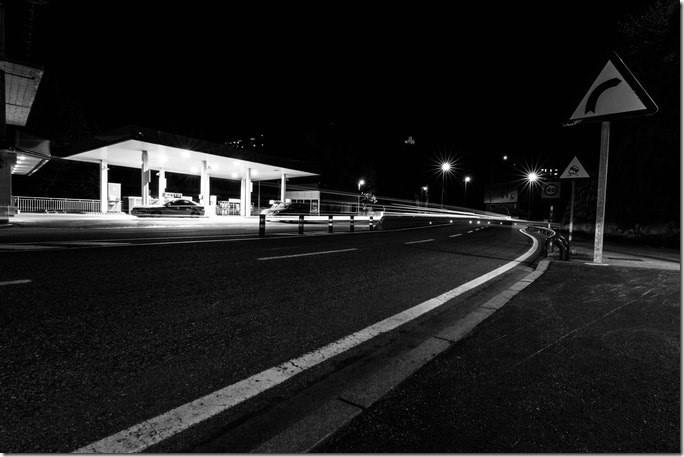

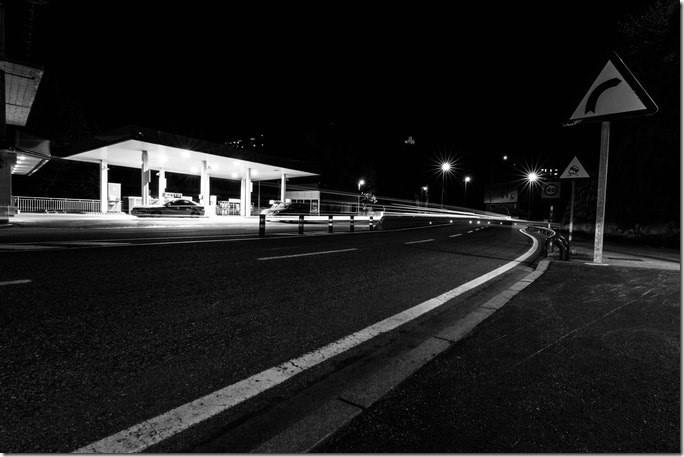

The door groaned as she pushed her way out into the cool late-night air. He was already in the car, the engine was running. He’d done his snack shopping, paid — or killed the attendant — and come back out to the car all while she was washing his hands. She’d kept him waiting. “Sorry,” she said, as she slid into the restored two-tone Bel Air.

Oberon was reading a map, a paper map, half-folded and well-worn. He intoned, “Mm-hmm”, and kept reading.

There was a white plastic bag stuffed with junk food on the seat between them. She started picking through the bag: two cold and dewy Cokes, a bag of Funions, M&Ms, some generic licorice, some—

His hand was around her wrist, pulling it up to where the light coming in the window played across the abraded skin of her palms, her knuckles, the top of her hand. “What’s this about?”

“Nothing. Let go.” She tried to pull away, but his grip increased immediately; he was much stronger than her, stronger than anyone she’d ever known. “Please.”

“No human could have hurt you like this; you must have done it to yourself. So why?”

“No reason. Just washed them a little too hard is all.”

“A little too…” He let go, but he stared while she tore open the licorice package and pulled one out, nibbling at the end of it. “You’ve washed your hands twenty times since we left Chicago. Maybe more that I’ve missed. You’re washing the skin off. Is this new behavior or is this something you do? Tell me.”

He was the King. “It’s new.”

“Since when?”

“Since I killed the pig.”

“Since you beat the store manager to death—”

“Yes.”

“—with your hands. Those hands.”

“…yes.”

“Which I told you to do.”

“You commanded it.”

He put the car into gear and let it roll forward on idle, until the front end crossed from the concrete deck of the service station onto the asphalt roadway, and then casually shifted into gear. She was pressed back into the seat as the car accelerated up the ramp and onto the highway. Finally, when they were in the left lane, at eighty miles an hour, he answered, his voice clear even over all the noise. “I did.”

“Yes.”

“And you obeyed, and you’d never done something like that before, and now it plagues you. You look down at your hands and they’re caked with his blood and his brains and bits of his skull and clumps of hair, and you have to get it off, but it won’t come off. So you keep washing them and washing them because maybe this time.”

She said nothing.

“When I was young,” He said, and then trailed off. He reached into the bag without looking, pulled out a coke, popped the top, and took a swig. After smacking his lips, he continued, “When I was young, they were still just animals. Hairy, stupid, tree-swinging animals. I called him a pig, right? No better than a pig. No worse, mind you, but still.”

“Pigs can’t talk.”

“Pigs can’t pin you against the wall in the stock room and shove their hands up your sweater. Pigs can’t—”

“Okay.”

“You know why they’re everywhere, now, the humans? The pig, his mother, his aunt, his cousin with the oxy addiction and his racist grandma? Do you know why we don’t rule this world?”

“No…”

“Because we fought amongst ourselves. Because we were busy doubting ourselves, doubting each other, and we didn’t notice the creeping rot of humanity spreading across everything. Look around you. I mean it, look.”

The highway had taken them out between towns, past even the developed farmland, but still there was the glow of human lights, everywhere, in all directions. It drowned the pinprick light of the stars in a morass of featureless grey. Only the moon stood out.

“Here’s the bad news: this is the Faerie Kingdom. This is. We’re driving across it, right now. But we’ve lost it, to them. Understand? We’ve been conquered, overrun. They’ve paved over our fields and painted strip malls across our sacred places. Their sewer pipes carry their stinking shit through our earth. Ready for the good news?”

She nodded, unable to speak.

“The good news is this: we can get it back, and it can be the way it was before. There are more of us now than there ever were, even then. Not as many as there are of them, but that doesn’t matter. And you know exactly why, because you killed the pig.”

“I don’t—”

“Was it hard?”

“What?”

“Was it hard to kill him? I don’t mean emotionally.” He took another swig of the Coke, a long gulp, raising it, upending it until the last drops emptied down his throat. He set the empty can carefully back in the bag. “Was it physically difficult to end his life?”

“No.”

“No?”

“No. I hit him once and he was on the ground. He hit the edge of the office door, it was open, you know, and he went down hard. I think he was stunned. He looked surprised. He looked confused.”

“Sure.”

“And I just kept hitting him until... until I felt, I don’t know, done.”

“You lived among them. I mean, we all do. To one extent or another, we have to. But you lived like one of them. That can poison your perspective. Gimme the Funions.” He held out his hand, and she ripped open the bag and handed it to him. “Thank you. Soon we’ll be home. I mean, my home, our home, for now, anyway.”

“Okay—”

“You’ll live among your own people. Where before there was only the banal scourge of humanity you will find the magic and wonder of your own kind. And believe me,” he tossed a Funion into his mouth, “killing the pig won’t bother you anymore.”

“Okay.”

“Until then, just, less washing your hands.”